The programme for this year’s research seminar series can now be downloaded here: Cesma. We welcome anyone who is interested in the interests and concerns of the Centre for the Study of the Middle Ages.

‘More Facts and Less Mudslinging’: PG Workshop in Pre-Modern Public Health

Postgraduate Workshop in Pre-Modern Public Health, hosted by Professor Guy Geltner

Danford Room, Arts Building room 224, Tuesday 17th October, 9am-11am

Following on from the CeSMA seminar on Monday 16th October, Guy Geltner of Universiteit van Amsterdam is hosting a workshop which aims to address, and potentially revise, medieval cities’ poor reputation for cleanliness and hygienic proactivity. Through an examination of primary source material we will think about the implications and possible connections that come from reading such documents, as well as the methodologies and theoretical approaches that underlie them.

In order to get the most out of the workshop, attendees are asked to complete the pre-reading of both the primary source material and the two secondary texts. More details of the workshop and the pre-reading are contained in the files below:

Premodern Public Health Workshop Birmingham Overview

Chew and Kellaway London Assize of Nuisance

Kowaleski Reader on Urban Hygiene

Dean Reader on Netezza Urbana

Rawcliffe 2013 Urban Bodies

Geltner 2013 Healthscaping a Medieval City

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Placement: End of Research

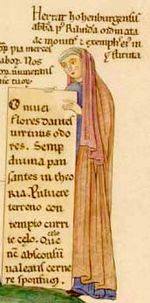

Over the past five weeks, I’ve worked on an UG Research Scholarship related to Emily Wingfield and Elizabeth L’Estrange’s project on “women and the book”, that looks at the legacy of Susan Bell’s 1982 ground-breaking essay about female book owners and readers. In this blog, I will talk about how the project has been a great opportunity that has helped me to improve my research and linguistic skills and find out more about woman’s relationship with written culture in the European Middle Ages.

During the project, I’ve researched sources about Italian, Spanish, German, English, Welsh, Dutch and Scandinavian women who often proved to be voracious readers, scribes, writers and translators of secular and religious books. This, despite the fact that, at the time, many men thought that women did not need to learn how to read and write and that the only books suitable for women were religious works. At the beginning of the project I focused on Germany, Spain and the Netherlands. I found several examples of German religious women who read works in Latin and vernacular, who were scribes, translators or wrote original compositions, such as Herrad of Landsberg (12th century) who wrote the Hortus deliciarum. In Spain, from the 11th to to the 16th centuries there were several examples of women writers and educated women, such as the Arabic-Spanish poetess Wallada la Omeya (11th century), the poetess Florencia del Pinar (15th century), Elvira de Guzmán (16th century) who owned a very well-stocked library and Luisa de Medrano (16th century) who taught rhetoric at the university of Alcalá de Henares, near Madrid. In Holland, in the 14th and 15th centuries, because of the higher demand for books and the increase in manuscripts and the production of religious books, the female members of the Devotio Moderna helped in the production of vernacular literature; laywomen also started to be part of craft guilds that were involved in the production of books.

Following this, I started to focus on Italy, England, Wales and Scandinavia. In Italy, especially in the 16th century, there were many examples of educated women such as Ippolita Sforza, Laura Cerata who wrote a letterbook, and Cassandra Fedele who debated philosophical and theological principles with male intellectuals. Moreover, I also found examples of women who worked as printers, publishers and booksellers between 1475 and 1620. Concerning England, I especially found examples of women translators such as Mary Bassett who translated the first five books of Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History from Greek into Latin and English. An example of a female Welsh writer of the Middle Ages is Gwerful Mechain who composed her works between 1462 and 1500. In Sweden, the most famous figure and the one that I focused on was Queen Christina (1626-1689).

Researching “women and the book” for five weeks gave me an insight into the research world. For an undergraduate student, five weeks of research might sound like enough time to achieve a more than satisfactory conclusion. However, once I was done with my project, I realised that there were still some gaps that needed to be filled and that even the research of only one topic can be really vast and diverse. This project taught me that it is important to be flexible and open-minded. The research, sometimes, might not lead to what you expected. In these cases, it is important to be ready to change perspective, think about which way the research is going and go on with the project. Moreover, this European-wide research gave me the opportunity to read articles in different languages and to think about the similarities and differences between the different countries, but also between the different periods of the Middle Ages. Therefore, the UG Research Scholarship gave me the possibility to improve my linguistic and research skills that will surely help me with my further studies.

In conclusion, this project gave me the possibility to improve my academic skills, and at the same time it allowed me to find out more about “women and the book” in the Middle Ages which is a really interesting and fascinating topic that should receive more attention. I would definitely recommend the UGRS scheme to future students. It is a great opportunity that really helps you to develop important academic skills.

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Placement: End of Research Summary.

Over the past 6 weeks, I have researched the topic ‘women and the book’ from 900-1600. This research has led me to investigate the role of women and book usage across Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and Asia. This blog will discuss what I found in Europe and how scholarship in this field can progress forward. Overall, this blog will argue that a more interconnected understanding women’s book usage is needed, which demonstrates the commonalities between the experiences of women and books in the medieval period.

In my analysis of European women, I focussed upon how women have been understood in the historiography outside the Anglo-Burgundian axis across England, France and Germany. To do this, I analysed Muslim and Jewish women in Europe and how these women used books in the different parts of Europe they lived him. Naturally this took me to the Iberian Peninsula, which had high Muslim and Jewish populations in the medieval period. In analysing the Umayyad Caliphate and the various Sultanates that emerged in the later medieval era, I found that Muslim women, as examined by K. Shamsie, occupied an important role within the libraries of the Sultan in collecting texts, analysing them and copying them to increase their availability. I found that Jewish women living in this region, as analysed by J.A. Harris, also used books within the domestic sphere reading the Haggadah genre within the home. Moreover, the role of women as teachers also became prominent in educating children on the texts they studied and religious texts which were considered important for spirituality.

After researching Iberia, I analysed women’s book usage on the peripheries of Europe in Ireland, Scandinavia and Turkey. In Ireland, the image of the reading woman on tombs was a powerful image with this put on the tombs of elite women throughout the medieval period as demonstrated by T. Martin. Therefore, the relationship women had with books was socially powerful, which went beyond the reading of text. Within the Scandinavian context, I analysed the figure of Dorothea of Brandenburg and how she, through her political power, established the University of Copenhagen in the fifteenth century. This research by K. Hundahl and L. Kjær, highlighted the intricate relationships between knowledge, books and political power. In Turkey during the Ottoman Empire, in the sixteenth century I analysed the poetess Mihri Hatun and how, from her elite background, she could write poetry which got the recognition of Sultan Bayezid II despite other male poets heavily criticising her work. Consequently, this research discussed in a study by S. Faroqhi details the challenges women faced in publicising their work and how they overcame these obstacles. Given this, I am sceptical that it can be argued that women had the same, widespread relationships with books that men did. This is due to the many restraints, highlighted in the examples I came across, that men enforced upon women.

My research within Europe has demonstrated not only the variety of ways women used books beyond central and Western Europe, but also the diversity of the women using these books at Europe’s peripheries. Such an understanding is also emphasised beyond Europe, into the Middle East, North Africa and Asia. Therefore, the research of women’s book usage requires a more interconnected and interdisciplinary approach, looking at the commonalities between practices rather than taking a nationalistic perspective. Such an analysis would consequently understand this subject within a cross continental approach, breaking down the boundaries enforced upon the past by historians.

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Placement: Isabel I of Castile and education

Isabel I of Castile (1451–1504) was an educated queen of Spain who surrounded herself with female scholars, advisors and teachers. As a child she received a brilliant education. She studied grammar, art, history, philosophy, music and poetry. She could also speak French and Italian and when she became queen she decided to study Latin so that she could personally take care of her diplomatic affairs and study classical texts in more depth. She owned 400 books which demonstrates that she must have been a voracious reader. In her library there were books in French and Italian, classical texts, history and religious books, books of entertainment and Spanish literature. Her oral and written skills were admired by scholars. Marineo Sículo and Francisco de Oviedo, royal chroniclers, affirmed that Isabel’s oratory grasped everybody’s attention. She also made sure that her daughters received an excellent education. When her daughters got married, they followed their mother’s example and surrounded themselves with a female educated court.

Isabel’s female courtiers’ interaction with cultural life extended beyond that of the court. They acted as patrons and promoted artists and cultural movements with which they shared the same ideas, but they were also educated women who dedicated themselves to reading and writing. Some examples of educated court ladies were María Pacheco who studied Latin, Greek and maths, Ana Girón de Rebolledo who was a voracious reader and was praised by Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, a Spanish poet and diplomat, for her intelligence, and Beatriz Galindo who was known in Spain because of her talent in classical studies. For this reason Isabel asked her to become her Latin teacher. During her stay at the royal court, Beatriz collected 126 books and founded a classical academy where scholars met in order to analyse classical texts. She also wrote two books, Comentarios sobre Aristoteles and Notas Sabias sobre los Antiguos.

Isabel promoted education in her family, in her court and in her kingdom. In this period women’s intellectual participation in society became more consolidated and there was a development of feminine literature and culture. Isabel favoured the establishment of girls’ schools and improved universities all over Spain. Therese Oettel affirms that in 1488 in the University of Salamanca there were more than seven thousand students, among which there were also women. Clara Chitera, for example, was enrolled at the University of Salamanca in 1546 and there she studied medicine, maths and also published a mathematical treatise. Therefore, Isabel’s educational policy and interest in culture, helped to develop women’s involvement in cultural life both in the court and public environment.

Sources Consulted:

Oettel, Therese. 1935. “Una catedrática en el siglo de Isabel la Católica: Luisa (Lucía) Medrano.” Boletín de la Academia de la Historia : 107-120

C, Segura Graiño. 2006. Las mujeres en la época de Isabel I de Castilla (women during the reign of Isabel I of Castile), Anales de historia medieval de la Europa atlántica: AMEA, Vol. 1, pp.161-187

M,Walliser (1996) Recuperación panorámica de la literatura laica femenina en lengua Castellana. (hasta el siglo XVIII). (Overview of women’s secular literature in Spanish) PhD Thesis, Boston College, pp. 137-231

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Placement: Italian Women’s Writings in the Medieval Period

Adnan Khan discusses his research on women’s book usage in fifteenth and sixteenth century medieval Italy.

With this project aiming to analyse female book ownership in Europe and beyond, Italy is one of the most important regions to be considered by historians given its central role in the Renaissance. This blog will highlight the research undertaken in this interdisciplinary research project in understanding what work on this topic has been done in the secondary literature, and the areas of analysis in this field that still require investigation. The picture below shows Florence, the birthplace of the Renaissance.

In the study of women’s book usage in Italy in the medieval period, historians have focussed considerably on the ‘long sixteenth century’. The period from 1580-1630, saw 66 single authored works written by Italian women. These varied in form including epic poems, pastoral dramas, tragedies, romances, and secular and religious works. This period therefore saw women become established in literary genres which had been previously dominated by male writers. However, this process of larger female book writing and usage can be understood further back than the sixteenth century alone, with important developments starting in the fifteenth century.

As has been studied by Virginia Cox, female book writing was a process that started far earlier in the Renaissance than has previously been stressed by scholars. Prior to the Renaissance, women had undertaken some religious writings however within the secular genre that emerged in the fifteenth century a new secular, cultural profile was created which Cox’s terms ‘the learnt woman’. This new profile that developed meant that it became socially more acceptable for women to write books alongside men, with this flourishing in the following century.

Two pioneers of the female women’s sixteenth century writings were Veronica Gambara (1485–1550) and Vittoria Colonna (1490–1547). Gambara was born in Pralboino and received a humanist education studying philosophy, scripture, theology, Greek and Latin. Gambara wrote many poems, with 80 of these available in English translation today. Colonna was also a highly influential poet from Pescara writing five major collections of poetry such as the Rime de la Divina Vittoria Colonna Marchesa di Pescara. However, from Cox’s research, she has found that both these women are genealogically connected to notable dynasties of “learned women” like the Nogarola of Verona and the Montefeltro of Urbino living in the fifteenth century. Therefore, the cultural profile of ‘the learnt woman’ created by the female elite in the fifteenth century saw the emergence of the vast literary works of similarly elite women in the following century. Yet, the image of the learnt Renaissance women was always restricted to the elite woman who had the opportunity to write and use books from the humanist education they received. How far this stretched to the poorer and less influential members of Italian Renaissance society however needs to be addressed by scholars despite the limited evidence available.

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Placement: Women’s Book Ownership and Representations of Piety in Fifteenth Century Ireland

Within the historiography of medieval women and book usage, Ireland has been overlooked given its location on the western periphery of Europe. However, as this blog shall demonstrate, the representation of books on the tombs of women was an important part of medieval Irish society and offers a unique perspective into the relationship between women and books in Europe.

As reflected in research undertaken by Therese Martin, in the late fifteenth century images of books on women’s tombs became a method of showing high social status and class. Martin, who includes examples of these tombstones, discusses how images on the tombs depict the deceased aristocratic woman holding an open book as if reading. The elite woman’s stance in this image represents piety but also the religious awareness of the woman. The example highlighted by Martin shows the woman surrounded by female saints holding closed books, again highlighting the religiosity of the deceased woman.

The representation on tombs of female book usage and ownership was not only to represent the women herself, but also the family she came from. The implied book ownership was a symbol of wealth and class as books were expensive in fifteenth century Ireland and not everybody could read. Martin highlights how in later medieval, European images and scriptures on tombs of deceased women reading were more common than in the Irish context. Therefore, this highlights the flow of these ideas of representation across Europe arriving in Ireland and being adopted. Martin argues that even amongst upper class Gaelic families in Ireland, literacy was low amongst women with women barred from bardic schools.

From the examples highlighted by Martin, it could be argued that some elite women in late medieval Ireland used books in their lifetime within a religious context to achieve piety with this depicted on their tombs. However, the more likely explanation is that most elite women in Ireland did not read religious texts given their inability to access education with the tombs reflective of the status of the deceased woman’s family. Therefore, although in practice most Irish women even on the elite level did not use books themselves, the relationship between the book and women is present nevertheless and portrayed powerful social messages of family and status. Thus, as demonstrated by Martin, the relationship between women and books can be analysed even if women themselves did not use books. Consequently, this method of analysis is a useful way of studying this field and should be applied in future research.

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Placement: Women and the Book: 900-1600 CE

In the last 35 years since the publication of Susan Bell’s pioneering article on, ‘Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture’ scholars have investigated the ways in which women across Europe interacted with books. This interdisciplinary research project, supervised by Dr Emily Wingfield and Dr Elizabeth L’Estrange, is encouraging two students to push the boundaries of existing research by investigating what historiography currently exists on this topic and the different pathways new areas of research can take. Claudia and Adnan discuss their experiences thus far, highlighting the directions their research is taking them.

Claudia Chiarenza

In the first week of my research, I have been looking at sources concerning women and books in Germany and Spain. The results have been really interesting. This research has shown women were not only readers, but also writers and scribes. In the Middle Ages, religious women had a greater access to written culture than laywomen. These women did not only read religious works but they also wrote original compositions. A few examples are The Book of Special Grace and Herald of Divine Love written collaboratively by an indeterminate number of nuns, in the Cistercian monastery of Helfta, in Saxony, and The Hortus deliciarum written by Herrad of Landsberg. An example of nuns as scribes can be seen in the Donenkron prayer books from Wienhausen. The nuns wrote these smaller books for their individual use. It is fascinating to think that these manuscripts could be evidence of the nun’s unauthorised devotional literature since, fourteen years after the reform of 1469, the Benedictine abbots visited the convent and stated that books of private prayers had to be examined and approved by them or their [male] adviser.

In Spain, in the late Middle Ages, the only recommended books for women were prayer books. However, one can see that women of the time also owned and wrote books that were not for religious uses. Some women wrote texts in which they expressed their own opinions. Such women did not follow what was considered a ‘good’ female education and wrote books that were not accepted by the Church. La ciudad de las Damas by Christine de Pizan is considered the starter of “la querella de las mujeres”, a cultural, political and social debate that stated the importance of women’s education and defended women’s intellectual abilities. Therefore women, despite the patriarchal societies they found themselves in wanting them to have a passive role in cultural life, tried to stand out and write their own literary works or devotional books.

Adnan Khan

Within the first three weeks of the project, I have focussed my research upon medieval Muslim and Jewish women’s writings around the Mediterranean. I have developed an annotated bibliography, detailing some of the most important works in the historiography across the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, the Levant and North Africa. From this research, I have found that comparing the development of women’s writings between these regions could be a new way of understanding this process as oppose to strictly national or religious lines. Therefore, I have drawn from my analysis on female book usage that different communities used books similarly in places like eleventh century Egypt, with high Muslim, Jewish and Christian populations, despite their religious differences.

In tenth century Iberia, I have found examples of exceptional women like Lubna of Cordoba. Lubna worked in Cordoba in the libraries of Caliph al-Hakam which contained over 400,000 books. Whilst also working as a poetess, Lubna was a copyist reproducing, like 127 other women in Cordoba, the Quran, the works of Aristotle as well as other texts found in the Caliph’s library. Lubna also taught boys and girls in Cordoba’s local schools and was described in Ibn-Bashkuwal’s twelfth century biographical dictionary as, “an intelligent writer, grammarian, poetess, knowledgeable in arithmetic, comprehensive in her learning; none in the palace was as noble as she.” Lubna rose to become Head of the Library and Private Secretary to the Caliph himself. Lubna was not the only woman to reach such heights in Cordoba. Fatima, who was Lubna’s contemporary, was tasked with travelling to the book markets of Syria, Iraq and Egypt to buy books for the Caliph’s library at a time when books were considered more precious than jewels. Therefore, despite the limited sources available, snapshots of active and significant Muslim women’s participation in book writing can be found in Europe in the medieval period.

Undergraduate and Postgraduate Research Placement: The Writings of Anna Comnena in 12th Century Constantinople

Adnan Khan shares his research on Anna Comnena and her writings on the Byzantine Empire.

This blog investigates European, medieval women’s writings on the edge of the continent in what is now present day Istanbul, Turkey. With much of the historiography on women’s writings in Europe focussing on an Anglo-Burgundian axis in Western Europe, this blog seeks to highlight the research that can be done outside of this. This blog will focus on the case study of Anna Comnena, and how her works represent the opportunities for Byzantine women to interact with book usage and writing.

Anna Comnena, 1083-1153, was born in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Anna was born in purple being the daughter of Emperor Alexios I and, given this privileged upbringing, was taught through a monastery studying history and philosophy and the work of scholars like Aristotle. Anna wrote histories on her father’s rule, documenting political events some of which she saw first-hand. These histories have been collated and translated into English in The Mexiad of the Princess Anna Comnena. These works sort to venerate her father above his successors with Anna’s analysis on the First Crusade one of the few Byzantine accounts still available.

Anna’s emergence as a historian was not common within twelfth century Byzantine society, despite her elite upbringing. A princess typically did not comment on the life of an Emperor and record this down for future generations to read. Anna was known throughout Constantinople for her intellectual capability and her knowledge of political and Christian practices which is highlighted by accounts provided by Anna’s contemporaries such as the Bishop of Ephesus, Georgios Tornikes. Furthermore, when Anna’s husband the historian Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger died in 1137, Anna would go onto finish his incomplete works in Greek documenting relations between the Byzantine Empire and the West.

Therefore, Anna is an example of a Byzantine women who given her elite birth was able to act beyond the expectations of her as a princess, completing some of the most important historical writings in the period. Furthermore, Anna was able to do this based upon her intellectual ability which reflects upon Byzantine society with similar examples available from other regions of Europe like Italy and Spain. Yet, the importance of Anna’s writings in documenting the life of the Emperor is an exceptional case which with further research may find parallels in other neighboring regions in the Middle East and beyond.

‘Fifth Annual Medieval and Renaissance Symposium’, St Louis University, Missouri, 19th – 21st June 2017

The Symposium is now in its fifth year and its stated aims are: to provide a convenient summer venue in North America for scholars in all disciplines to present papers, organize sessions, participate in roundtables, and engage in interdisciplinary discussion. The promotion of serious scholarly investigation into the medieval and early modern worlds was at the heart of this Symposium.

We formed a panel entitled ‘Interacting with Saints and Shrines: Text, Image and Material Cultural’. The session explored engagements with cults and shrines in a variety of contexts and media, with specific focus on the cult of St Æthelthryth of Ely; the Cistercian Order in the twelfth century; and southern Italian shrines in the high Middle Ages. The papers demonstrated how images, material culture and texts were utilised to portray saints and engage with the lay communities, thus ensuring that the religious institutions’ messages were heard and disseminated. Thanks to conference travel grants from CeSMA, the Royal Historical Society, and Midlands3Cities, we were able to participate in this international conference to present the paper and take advantage of the networking opportunities offered by this established Symposium.

The meeting included plenary sessions by Bruce Campbell, Christopher Baswell and Damian Smith. Campbell’s talk entitled ‘Unemployment, Leisure and Industriousness in Late-Medieval and Renaissance Europe built on the work of Phelps Brown and Hopkins from the 1950s which profiled daily wages from 1250 through to 1900. He advocated a more nuanced approach which incorporated detail relating to gender and geographical differences and the variation between real and nominal wages, highlighting anomalies in the traditionally held view. Baswell examined the depictions of disability in thirteenth century Arthurian romance literature, which up to now has been underexplored in scholarship and encouraged further work in the field. While Smith expanded on his current topic of research on James I of Aragon by considering the existing scholarship surrounding his legitimacy to the crown of Montpellier.

Unfortunately, several speakers were unable to attend which resulted in a number of panels containing only one or two papers. However a wide variety of subjects were explored in the papers we attended. Burnam Reynolds explored the appearance of celestial beings at the battle of Antioch and considered how and why such an account was accepted in Western Christendom; whether the Turin shroud was included in the booty from the fourth crusade was addressed by Thomas Madden; the change in crusading policy by Gregory X following the death of Louis IX was examined by Samantha Cloud; Cathleen Fleck analysed the depiction of Robert I of Naples as King Solomon in the Anjou bible, suggesting that it was an attempt to reinforce his rule on the Italian peninsula; and Anne Carmichael argued that the plague policy in 15th century Milan was not imposed from above but a result of a collaboration between the community and health officials. Throughout the Symposium the importance of best practice in presentation technique became evident as we observed the different styles used by the speakers.

The atmosphere throughout the conference was

collegiate with receptions on each evening providing the opportunity to discuss papers and research projects further. We have appreciated the chance to attend and present at this established Symposium and look forward to incorporating some of the ideas and methodology into our own research.

by Georgie Fitzgibbon